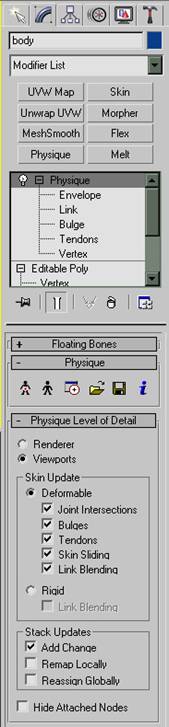

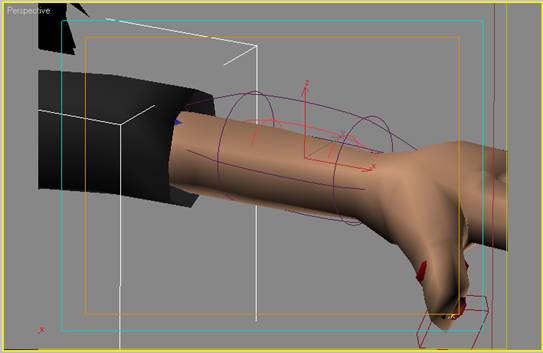

Getting to this point was quite a milestone, bringing Blender to the point of being a quasi level-editor with built-in character animation suite, both seamlessly integrated in my game development process. The development process was then quite streamlined: my workflow was reduced to just Edit->Export->Run, doing so over and over until things were working as close to 'right' as the current version now is. I found Cal3D worked fairly well with OpenSceneGraph via Loic Dachary's osgCal (OpenSceneGraph and Cal3D) library when using Marco Frisan's modification of Jean-Baptiste Lamy, Chris Montijin, Damien McGinnes and David Young's Cal3D exporter. Due to the fact I was using OpenSceneGraph so heavily in this project it was necessary for me to work with a compatible character animation file format. They were then all named carefully in a way that I could search for in code: 'r2t1' represents teleport 1 in room 2 whereas 'r4d3' represents the third door of room 4.Īfter that came character animation, something I'm reasonably bad at.

Once these were all in place I gave them a transparent material so they wouldn't be seen in-game. I also threw around a few other planes to help me position text that's dynamically rendered at runtime. I then made triggers in the form of planes for each door and small horizontal planes outside each door that would be used to locate spawn-points when the character moved from room to room. Looking closely at the openscenegraph (.osg) Python exporter I could see that object names were retained after the export, allowing me to search for them by name in my scene. The next day or so of work was focussed around setting up Blender as a 'level-editor', specifically for my game. By pairing up base meshes with radiosity meshes in this way I could make changes to the base mesh and re-bake if I needed to later (I find Blender's layers, available in every 3D viewport, to be a vital part of asset-management in complex projects). I then set up the meshes for radiosity and copied those baked meshes to the row below. Once done I started extruding stairs out, one face unit at a time. I then copied this base room mesh across another 5 layers in the same row.Īt this point it was time to work out where all the doors should be, including the doors which act as traps (illogical doors). Then I extruded all the faces back to create a box with an open top.

I then subdivded the cube such that a single face was the height of a step. The mask cube was used by the game renderer to mask out the edges of rooms, giving the appearance of the rooms being 'inside' the marked block the player holds. I made a 'mask' cube and put it in layer 20, then copied it to layer 1. I then set about making all the rooms, starting only with a cube. Scale and orientation were also relatively homogenous both sides of the export, something super rare in game development in general. The native OpenSceneGraph (.osg) format proved to be just what I needed, retaining the same look to my radiosity meshes as I saw in in Blender. My first job on the art side was to find a file format that Blender exported and OSGART (ARToolkit and OpenSceneGraph) liked. Blender proved to be perfect for this: it offered a wide array of exporters to try out-of-the-box, all of which were written in Python so I could fiddle with them if I needed to.Īs a game developer, this kind of hackability is invaluable. To these ends it was important that I could customize my export pipeline to suit the special needs of my project. Then, on the engine side, these triggers would be found in the scene by name and setup for use. I really wanted to use my 3D modeler as a 'level-editor' for this project, where I could lay triggers and spawn points inside the rooms and export it all out as a single file. LevelHead proved to be an ambitious little experiment that required solving head-scratching programming and design problems.

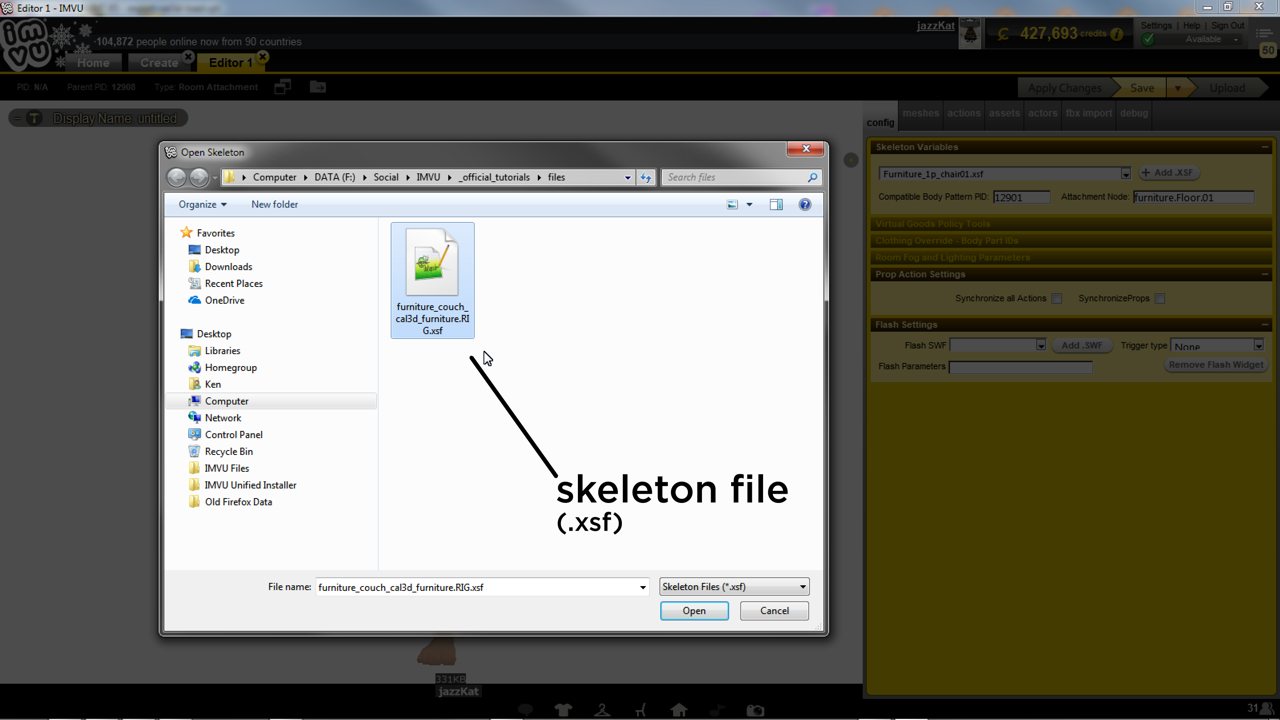

Cal3d exporter download#

You can watch the YouTube version, or download an OGG/Theora file which plays in VLC. Julian relied on Blender to create the interior of his cube and in this article he talks how Blender fits into his workflow.īefore reading the article, watch the video. There are five cubes (levels) in total and just as you imagine, the traps become increasingly difficult to avoid. You have just 120 seconds to find the exit of each cube and move to the next. Some doors lead nowhere and will send you back to the beginning. By tilting the cube you lead a character around the rooms. 'Inside' the cube are six rooms, each of which are logically connected by a network of doors. It uses a Sony EyeToy camera to capture the image and a screen to present the computed result

It uses a cube - with an image on each face - as its only interface. LevelHead is a spatial memory game by Julian Oliver.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)